When I picture myself during my first few days in Australia, I have to laugh. I am standing behind the stove in my in-laws’ kitchen, learning how to make coffee the Italian way, one strong cup at a time. I pour water into a tiny silver percolator, then spoon finely ground coffee into the sieve-like reservoir through which hot water will soon flow.

It’s a cozy scene, except for what I’m wearing: a skimpy undershirt and Daisy Duke cut-off shorts with my thong underwear protruding from the waistband. To see me, you might think I’m trying to show off my body, but that isn’t right. While in Jeffrey Epstein’s employ, I’d been encouraged to wear clothes that made me look even younger than I was. Now, no longer Epstein’s captive, I was a wife – a grown woman. But I still felt – and dressed – like a teenage girl. I didn’t have the slightest idea how an adult version of me should look.

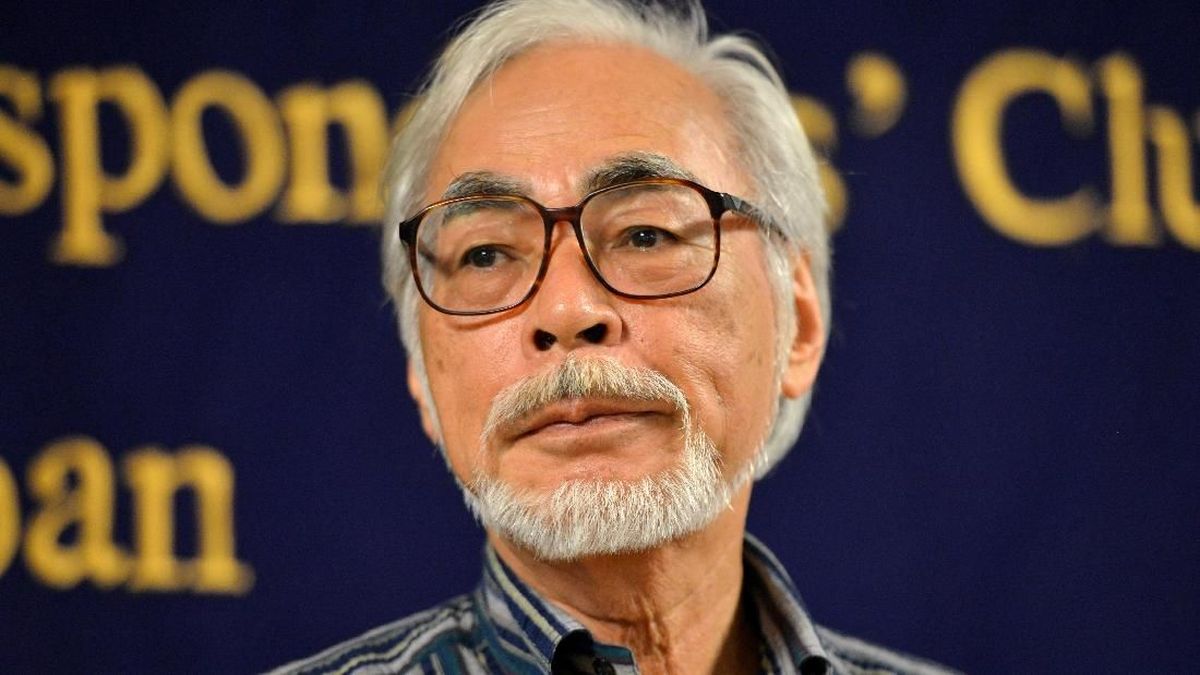

Jeffrey Epstein encouraged Roberts Giuffre to look as young as possible.Credit: FILTHY RICH courtesy of Netflix

When I moved into Frank and Nina’s house, that was just the beginning of what I didn’t know. I had never loaded a dishwasher, for example, or scrambled an egg or separated laundry into darks and lights. I’d never opened a bank account or filed income taxes or made a good cup of coffee – the list went on and on. Sometimes the weight of my ignorance overwhelmed me. What is adulthood, I wondered, and will I ever master it? What is it to be a wife? It would take time for me to figure out the answers.

Our first weekend in Australia, Robbie took me camping in Hunter Valley, north of Sydney, with a group of his friends. The place is one of the country’s major wine regions, but we had so little money that Robbie decreed we were there to rough it and enjoy the natural beauty, not to sip Shiraz. I was good with that until I saw where we were sleeping: a ramshackle shed. That weekend was quite an introduction to my new country. Yes, we saw a few Aboriginal cave paintings, but the weather was freezing and the only kangaroo we spotted appeared to have been dead for months.

Epstein began abusing Roberts Giuffre when she was 16.Credit: Virginia Roberts Giuffre

A few days after our return, I fell terribly ill with some sort of flu. When I spiked a fever, Robbie was at work – he’d gotten a construction job. I felt awful: clammy and hot. I didn’t want to be a pain in anyone’s ass, and – especially since I’d just learned the Aussie phrase “having a whinge” (complaining for no reason) – I was determined to be stoic. But when Robbie’s dad discovered how sick I was, he swung into action, whipping up his special zuppa di lenticchie, or lentil soup.

I was too weak to get out of bed, but Frank propped me up on my pillows and then sat beside me, feeding me spoonfuls until I was full.

Later, as I passed in and out of a sweaty, delirious sleep, he returned every few minutes to cool my forehead with a damp cloth. When my fever broke, Frank brought me coffee that was creamy from the raw egg he’d stirred into it.

He didn’t say much, just as Robbie had warned that he wouldn’t, but in those first weeks that I was in Sydney, Frank gave me more nurturing than I ever got from my own father.

In early 2003, Robbie and I moved into our first apartment in Parramatta, but I was still kicking an expensive habit – Xanax – that I used to help blot out my trauma. Back in Laos, I’d dumped most of my supply in a toilet because I feared that being apprehended with drugs might get us thrown in jail. But I still had a small stash, and it was running out. Not that I admitted this to Robbie. While I’d been honest with my husband about the range of damaging experiences I’d endured, I think he expected that the further away I got from those incidents, the better I’d feel. Instead, the opposite seemed to be happening.

Roberts Giuffre says she was trafficked to Prince Andrew (pictured) for sex three times. He denies it.

Memories I’d tamped down for years were now coming up, unbidden, in vivid detail. Disturbing images would pop into my head during the day – the black leather, studded collar Epstein had choked me with; the greedy, cruel look on the minister’s face as he watched me beg for my life.

I was haunted by nightmares – my abusers looming over me, about to pounce, and me unable to get away. Nevertheless, I was not yet willing to acknowledge how much pain I was in or how much I’d relied on antianxiety meds in the past.

One day Robbie came home from work and found me sitting on the floor in the corner of our apartment, surrounded by blood and broken glass. I had been cutting myself – not trying to kill myself, but instead using the clarity of inflicting my own pain to quiet my raging demons. When Nina arrived, she swooped in like a bosomy angel, kicking the shards of glass away and taking me into her arms. She must’ve held me for an hour, rocking me, telling me it would be all right. Then she took me to the bathtub, stripped off my clothes, and tenderly washed me as if I were her own child. Once again Robbie’s parents were giving me what I’d been missing since I was a tiny girl.

One day I walked by the living room as my mother-in-law was watching television. There, on the screen, was an actress who’d once been one of Epstein’s victims, like me. Now there she was on Nina’s TV. “How do you know her?” Nina asked, seeing my stunned face. I didn’t know what to say, so I turned and left the room.

Loading

Then, in March 2003, Vanity Fair magazine published a lengthy profile titled “The Talented Mr Epstein”. I don’t remember exactly when I first read it, but I do recall being shocked by its gushing tone: Epstein was described as “good-looking”, “charming”, “very generous”, and “like a king in his own world”; his Manhattan townhouse was like “someone’s private Xanadu”.

There was a reference to Epstein’s love of women (“mostly young”) and a description of his “complicated past” – a reference to some of his questionable financial dealings. But the article said many people had commented that “there is something innocent, almost child-like about” him. “Oh, is that what you call it?” I asked out loud. “Innocent?!” Then I threw the magazine across the room.

If you, or someone you know, needs support you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636.

This is an edited extract from Nobody’s Girl: A Memoir of Surviving Abuse and Fighting for Justice by Virginia Roberts Giuffre. Available now from bookstores, as an eBook and audiobook.