The activist, historian and author, 68, has written four novels, won major awards in three states, and twice been shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award. His new book is the story collection, Pictures of You.

Each week, Benjamin Law asks public figures to discuss the subjects we’re told to keep private by getting them to roll a die. The numbers they land on are the topics they’re given. This week, he talks to Tony Birch. The activist, historian and author, 68, has written four novels, won major awards in three states, and twice been shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award. His new book is the story collection, Pictures of You.

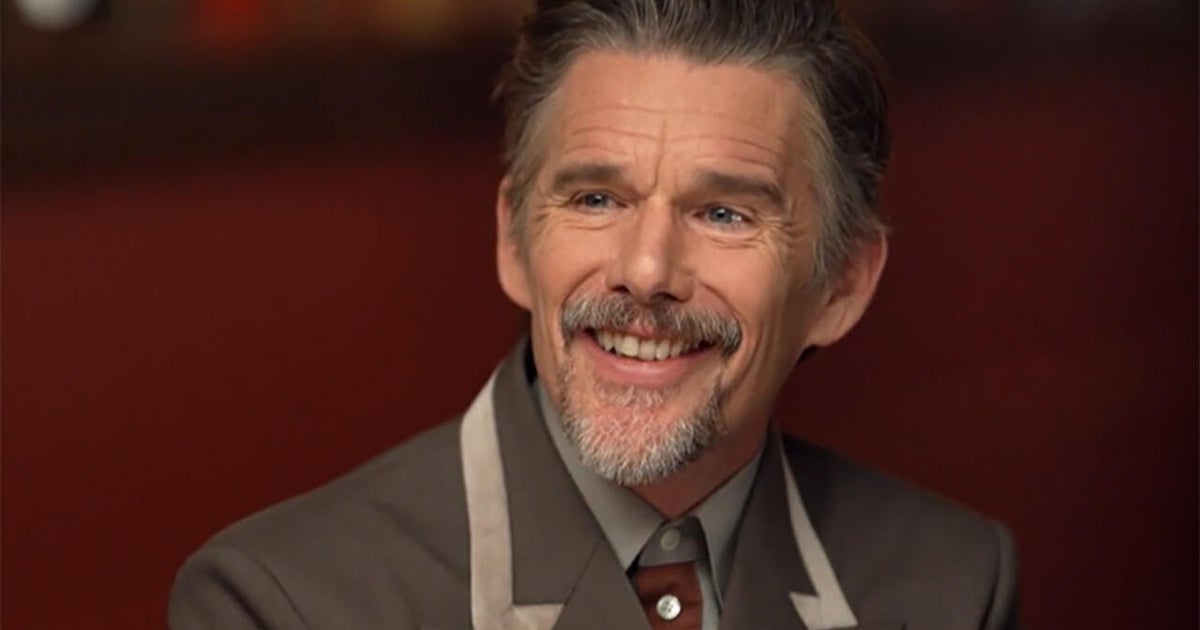

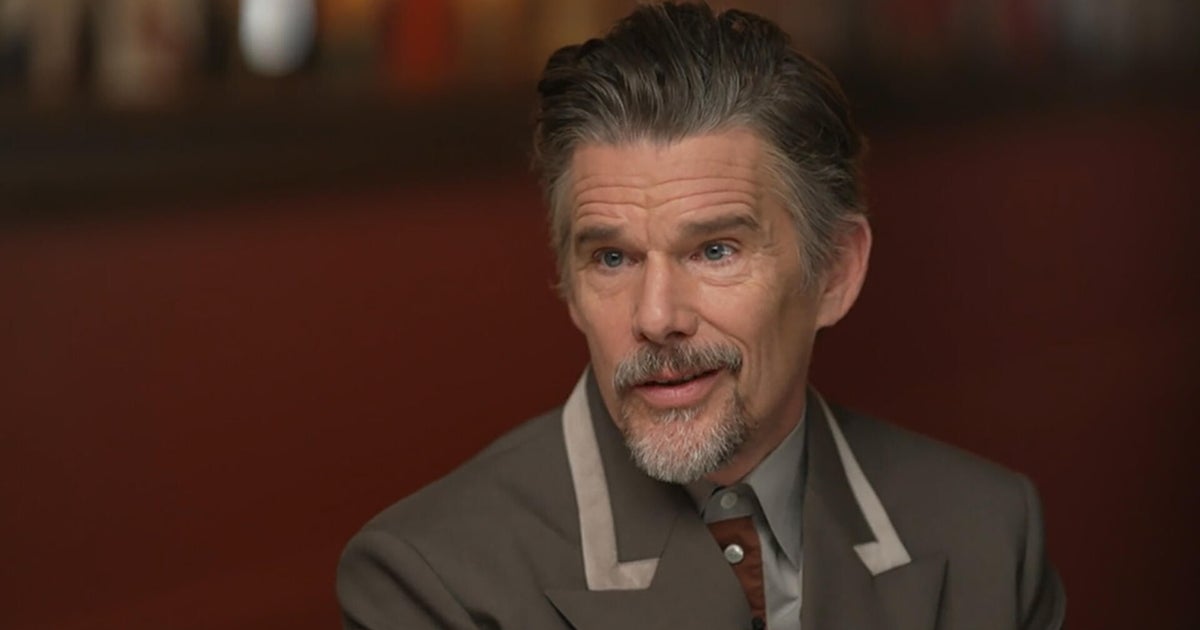

Tony Birch: “When you’re a long-distance runner, at some point in a run, your mind empties out of any problems and anxieties. It’s like you have this clean slate.”Credit: Benny Capp

POLITICS

“All writing is political.” Discuss. I’m often regarded as a political writer, but I’d never write an overtly political book. I write the story that demands to be written. The White Girl is clearly about the politics of race. In Women and Children, family violence – male violence – is always in the background. But that book is really about tenderness, and I hope that people regard my books as being more about love than violence.

The world is such a bin-fire right now and you’re a longtime activist on so many issues. How do you pick your battles? You can’t fight every battle; you can’t win every battle. But I will say that if I were to have a serious political battle, I’d never play it out on social media: it’s inherently destructive. You need to know when it’s your turn to listen, as opposed to your turn to speak. In regard to the shocking atrocities in Gaza, I’ve spoken on two or three occasions over the past couple of years, but only when I felt it was really important. I want to be an ally, not an orator.

Can you be friends with someone who doesn’t share your politics? Yeah, but there are limitations: I don’t have any friends who are Nazis. But you can have really important, rigorous, ethical discussions with people who you don’t agree with. That’s flexing your intellectual and political muscle.

Would you ever run for office? I’d never run for political office. I ran for class captain at [Melbourne’s] Richmond High, and I won. But the teacher vetoed it because she said the class wouldn’t be run by a juvenile delinquent. Oh, that bruised me badly.

MONEY

Is it true you grew up in slums? Well, if she heard you call it that, my mother would slap your face. But yes, I grew up in inner-city Fitzroy in the 1960s, and it was very impoverished. We lived in a one-bedroom house, which was really decrepit and rundown. My dad had a really poorly paid job as a council labourer and then a hospital cleaner, and my mum worked in the Harding’s crumpet factory in Richmond. I remember living on crumpets stolen out of a bin in the backyard of the factory. In fact, I could do a cookbook: 52 Weeks of Crumpets.

Do you remember when things changed, financially, for you? Yes. When I could walk into a bookshop and buy a book rather than borrowing it from the library. When I could go and see any film I wanted to see. When I started my first job as a telegram boy, I remember going with my first pay packet to buy clothes and records. I have to say, I was really pleasantly affected by my introduction to mass consumerism.

What’s the richest you’ve been? Probably now. I have a highly paid job as a professor of literature at Melbourne University. I own my own house in Fitzroy. I have really good superannuation. In a material sense, I’ve never been more well-off.

What does it allow you to do? I have five adult children and four grandchildren and it’s allowed me to be generous with them. Generous emotionally, I hope, but generous materially and financially, too. And if I win any [financial] prizes, I’ll always take money off the top and give it to an organisation for Aboriginal women escaping family violence.

Any money advice generally? All I’ll say is, if you have five kids, never send them to private school.

BODIES

You’ve been a serious runner since you were 18. Is there a relationship between running and writing for you? Absolutely. The way running functions in relationship to writing is in two ways. The first thing: when you’re a long-distance runner, at some point in a run, your mind empties out of any problems and anxieties. It’s like you have this clean slate. If I’m working on a novel or a short story and I’ve been dealing with a problem, that’s the moment ideas come to me. The other thing: I had back surgery in January this year and couldn’t run for six weeks. I became Mr Grumpy of the worst kind and couldn’t write. When I come home from a run, have a shower and sit down to write, I’m basically in the zone.

Is your body OK? Yeah. The surgeon, who was a lovely guy, deduced that it was a spinal injury resulting from 50 years of running. Then he suggested to me that I take up another, more passive form of exercise – and then he saw the look on my face. He said, “You’re not going to do that, are you?” I said, “No. I’ll see you in another 50 years.” But I did do all the physio and exercises that were required of me and I got back into the running very gently. As you get older, you run a lot slower, but as long as you don’t take a watch with you, you have no notion of that.

Loading

When do you feel most comfortable in your skin? After a run or when reading a book on the weekend – sitting on the couch when it’s cold and wet outside.

When do you feel least comfortable? When I see inequality and I can’t alleviate it.

Which superpower would you want to have? I’d be Superman. I’d fly from Fitzroy to the White House, put Donald Trump in a headlock and not let go until he gave in.

Most Viewed in National

Loading