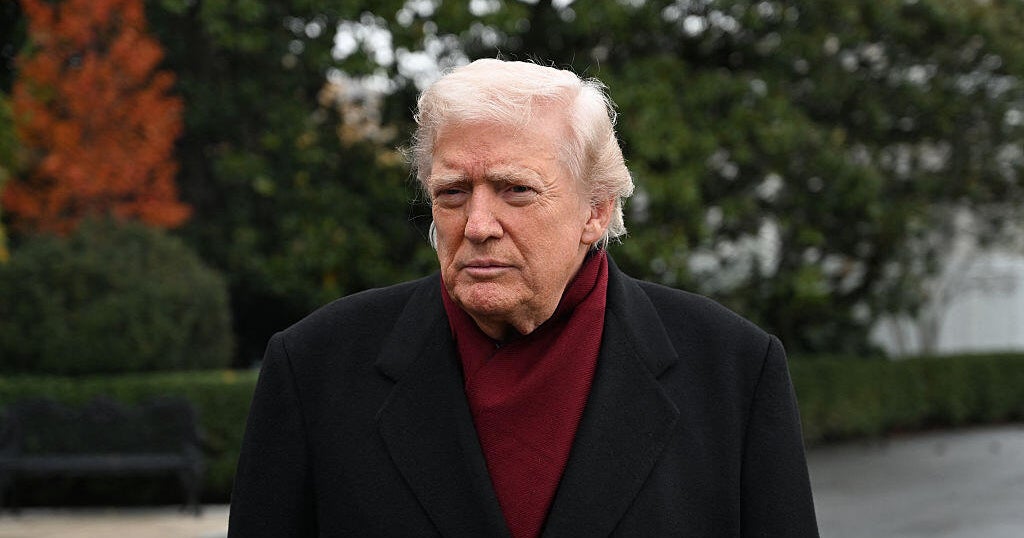

Truth and Donald Trump rarely move in the same circles.

When confronted with some unpalatable jobs figures last week, the president decided rather than acknowledge the American economy is not travelling as he would like, the solution was simply to shoot the messenger and sack the head of the Bureau of Labour Statistics.

Donald Trump and the truth … not seen often in the same circles.Credit: AP

Trump firing bureaucrats is nothing new. But in this case, there has been an almighty blowback among statisticians, economists and business analysts over what he did. Because while Erika McEntarfer was not a high-profile or particularly well-known figure to the American public, what she represented is exceptionally important.

McEntarfer’s sin was to release the regular monthly jobs numbers, a closely watched measure of the state of the economy. Unfortunately for the Republicans, the July figures showed that 73,000 jobs had been created that month. This was far lower than the 150,000 markets had expected.

More worrying, the bureau also reduced by 258,000 its estimate for the number of jobs created in May and June.

Loading

Taken together, these jobs numbers show a weakening American market. They also confirmed private estimates, and what is occurring across the broader US economy.

All of which was too much for Trump, who accused McEntarfer – who only a year ago was confirmed 86-8 by the Senate to take on the job – of rigging the numbers to make him look bad.

“Important numbers like this must be fair and accurate, they can’t be manipulated for political purposes,” he declared on social media without a skerrick of evidence of impropriety or irony.

In response, a group of statistical agencies that goes by the name The Friends of the Bureau of Labour Statistics released its own, more factual, statement that read: “This escalates the President’s unprecedented attack on the independence and integrity of the federal statistical system. The President seeks to blame someone for unwelcome news,” it said. It’s also worth noting that the group statement was issued by William Beach, who was McEntarfer’s Trump-appointed predecessor at the bureau.

US President Donald Trump speaks to the media after telling officials to fire Erika McEntarfer, the commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Photographer: Aaron Schwartz/CNP/BloombergCredit: Bloomberg

It’s hard to overstate what Trump has done. Imagine if Anthony Albanese decided to sack the nation’s chief statistician because the latest inflation data was not what the government wanted. There would, rightly, be an outcry.

Naturally, the Trump apologists have been out defending the indefensible, ignoring the fact that the bureau has always revised job numbers (up and down), no matter the occupant of the White House.

Last year, while Joe Biden was still in office, the bureau revised its jobs figures between January and July down by 340,000. But the single largest downward revision came in March and April 2020, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the number of jobs was cut by almost 925,000.

Loading

Revisions are part and parcel of what the Bureau of Labour Statistics does. Every month it updates its numbers as it receives more information. The monthly release, plus the revisions, are vital to policymakers (like the Federal Reserve) and investors so they can see how the economy is travelling in as close to real time as possible.

Ever since he declared a record crowd at his 2017 inauguration, Trump and reality have been at odds.

In the grand scheme of things, crowd size does not really matter. But using a Sharpie to extend the expected landfall of a hurricane, gutting agencies responsible for tracking climate change, and ignoring employment data have very real consequences.

Economists and policymakers have, for years, been worried about the statistics coming out of nations where the political leaders meddle with the numbers.

In Argentina during the 1990s, the government fired bureaucrats who released less-than-flattering inflation figures and began releasing their own (sound familiar?). Understandably, this made international investors wary and increase their premiums as protection. By 2001, the government was in a full-blown debt crisis and defaulted on $US93 billion of debt.

Greece, Turkey, Russia and China have also tried to play fast and loose with statistics over the years. It got to such a point in the case of China that outside economists used electricity consumption or satellite pictures taken at night (to see artificial light) as a de facto measure of GDP because their trust in the official numbers was so low.

As financial analyst Ned Davis told The Wall Street Journal, “Your initial thought is, ‘Are we heading toward what you see in Latin America or Turkey, where if the data doesn’t look good, you fire someone, and then eventually stop reporting it?’”

Just a few days before McEntarfer’s sacking, Trump was saying how great the economy was travelling – and demanding the Federal Reserve cut interest rates because it was going so well.

Of course, the GDP figures did not show that (growth is slowing while inflation, at 2.7 per cent, is above the Fed’s 2 per cent target rate). But Trump couldn’t admit that, so he told his own story.

Loading

Around the same time, the president claimed that his government had cut pharmaceutical prices by “1200, 1300, 1400, 1500 per cent. I don’t mean 50 per cent, I mean 1400, 1500 per cent”. And he’s the one who thought the Bureau of Labour Statistics was making up numbers.

The problem with making up your own numbers, or installing people who will make the numbers show what you want, is that they will be at odds with the lived experience of voters.

Just as Biden struggled to convince Americans that the cost of living was getting better while they could see the price of everyday essentials going up, saying the economy is great to people lining up for unemployment benefits has a short shelf life.

There’s an adage used by economists to describe the models they use to understand the economy: Put crap in, and you get crap out.

Now, we’re seeing crap being sprayed across the state of the American economy in real-time.

Shane Wright is a senior economics correspondent and regular columnist.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading