Sewage treatment should destroy fatbergs. Yet the horrifying conclusion of a probe into the source of the dark debris balls that washed up on Sydney beaches a year ago is that it is only a temporary blip.

University of Sydney wastewater engineering expert professor Stuart Khan, who has headed the NSW Environmental Protection Authority’s panel investigating the grime balls, believes the most likely source of the pollution is the deep ocean outfall attached to the Malabar wastewater treatment plant.

Like Bondi and North Head, the Malabar plant does only primary treatment, which removes solids but does not treat the effluent. Secondary treatment would remove fats, oils and greases through biodegradation treatment. Tertiary treatment would add another layer of filtration.

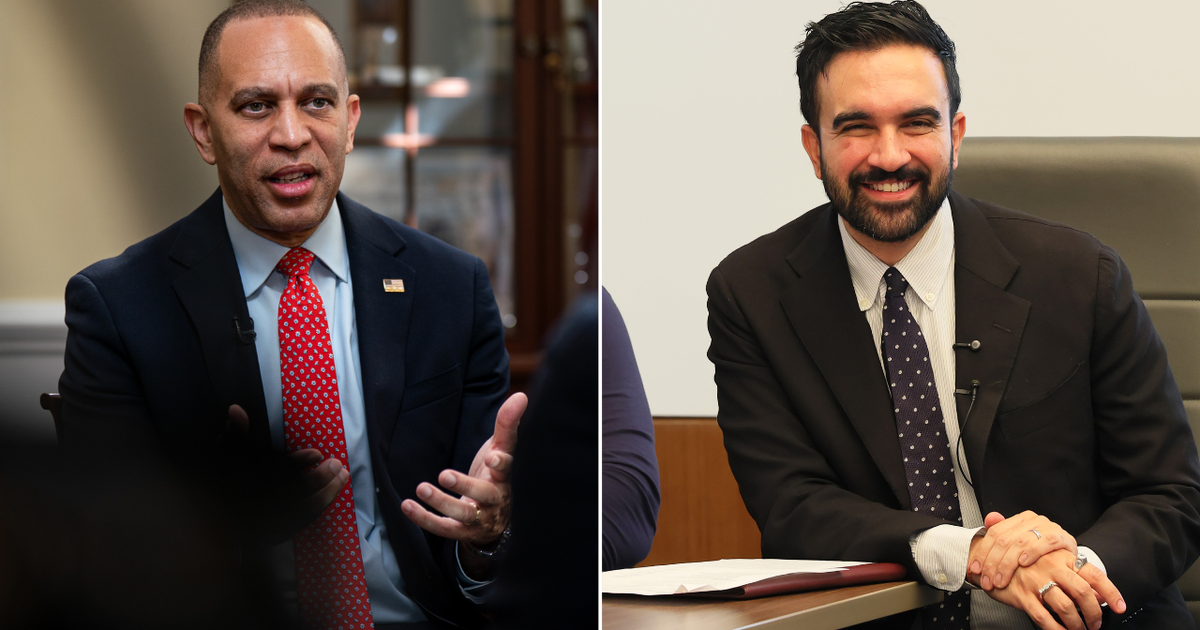

Scientists studied the composition of the black balls that washed up on Sydney’s beaches last October.Credit: Rhett Wyman

Fatbergs form when fats, oils and grease congeal into solids in cooler water and clump together with any debris such as wet wipes. Sydney Water says there are 20,000 blockages of fatbergs and wet wipes in the wastewater network every year, which costs $27 million.

“The screening process is quite fine, so something the size of the balls that we’ve seen shouldn’t make it from the sewer into the treatment plant at all,” Khan said. “It seems more likely that the debris balls that ended up on the ocean beaches actually came from the deep water ocean outfall itself.”

Khan said the most likely theory was that the fats, oils and grease suspended in fine particles in the water after filtration would congeal and form round balls in the four-kilometre long deep ocean outfall tunnel, shaped by continuously bumping the sides of the cylindrical pipes. However, as the outfall is below sea level, it was difficult to confirm the theory.

The EPA required Sydney Water to conduct various studies and investigations. The panel had considered those, Khan said, along with reports from consultants and independent testing of the composition of the balls, and hydrodynamic modelling to see how material would travel through the network and along the coastline.

Khan said the panel settled on Malabar as the likely source because the debris balls contained hydrocarbons consistent with the heavy industry in the catchment. The smaller primary treatment plants at Bondi and North Head mainly dealt with residential waste.

“Malabar drains wastewater all the way through western Sydney, all the way to Fairfield,” Khan said. “There’s a lot more industry, and the wastewater is actually quite different. The chemical analysis of the tarballs does seem to point fairly clearly to the Malabar system.”

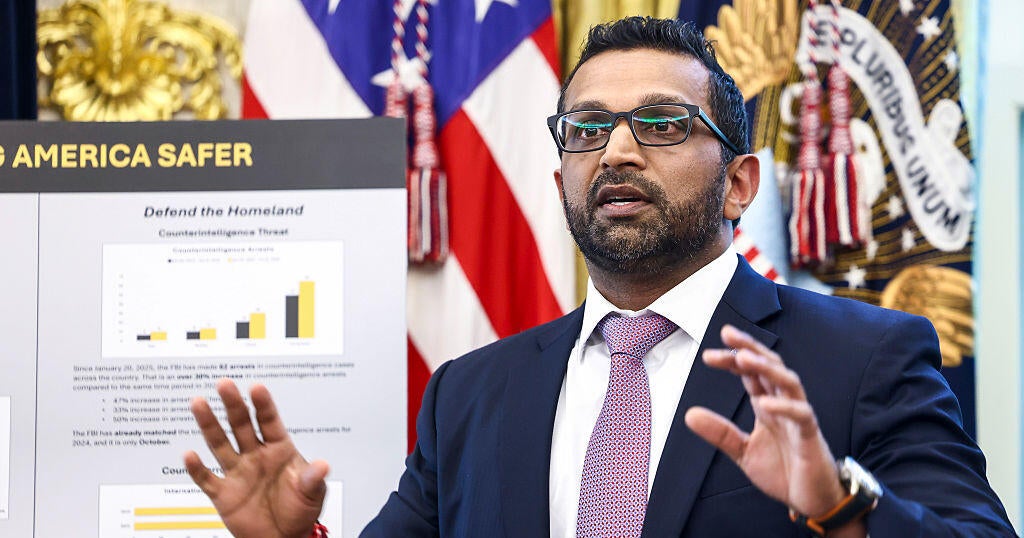

Workers in protective clothing clean up Coogee Beach after the debris balls were washed up.Credit: Dominic Lorrimer

The EPA confirmed in a statement that Malabar had been identified as the likely source of debris balls that washed up on beaches between October 2024 and February 2025.

The panel did investigate whether the debris balls could have formed upstream when heavy rain caused sewage to overflow into the stormwater system. Khan said the main possibility was Mill Pond, which regularly overflowed into Botany Bay because of the sheer volume of wastewater headed to Malabar.

The modelling suggested it was highly unlikely that the fatbergs could find their way from Mill Pond to Coogee Beach, where they were first found. While other sites in Sydney sometimes have sewage overflow, Khan said this happened only when rainfall was so heavy that the output of effluent would be extremely diluted.

Minister for Water Rose Jackson said in a statement that coastal treatment facilities operated under strict environmental controls.

“Sydney Water is now working to prevent future events through new programs to help reduce the amount of fats, oils and grease entering the wastewater system,” Jackson said.

“They also have a long-term plan to ensure the sewage system can meet the needs of a growing city and a changing environment.”

This included upgrades to the Malabar and Georges River systems by 2029, upgrades to the North Head system and a new facility at Camellia by 2031, and upgrades to the Bondi system, including diverting flows from Diamond Bay and Vaucluse by 2028.

Loading

Sydney Water was also working on recycled water schemes to reduce the volume of wastewater that needed to be treated and released into the ocean, Jackson said. However, the government is yet to approve purified recycled drinking water for human consumption.

Khan said it would be very difficult to upgrade Malabar to more advanced treatment given the space constraints at the site. He backed proposals to remove as much wastewater from the system upstream, and said enforcing grease traps at restaurants and cracking down on illegal stormwater connections would also help.

This masthead reported in May that the panel was investigating whether the source was the outfalls or stormwater, and that Sydney Water was pushing recycled water as the solution to reduce the volume of wastewater headed to sites such as Malabar.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.

Most Viewed in Environment

Loading