An international researcher whose work helped cast doubt over the scientific evidence for shaken baby syndrome has described an Australian court’s precedent-setting judgment as “ignorant and embarrassing”.

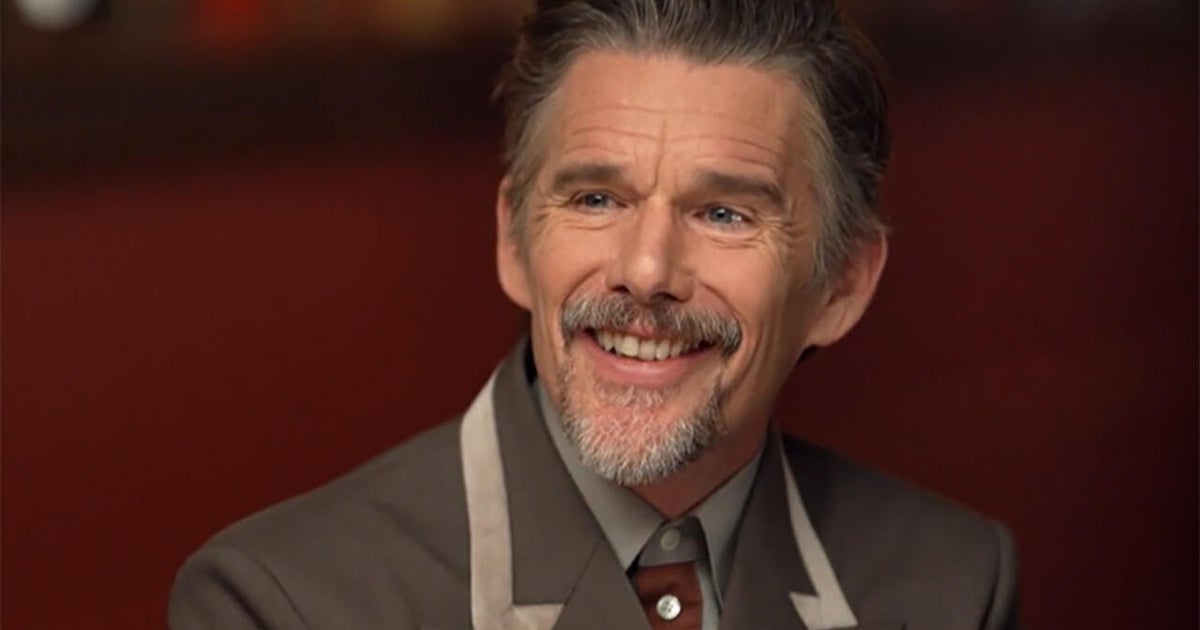

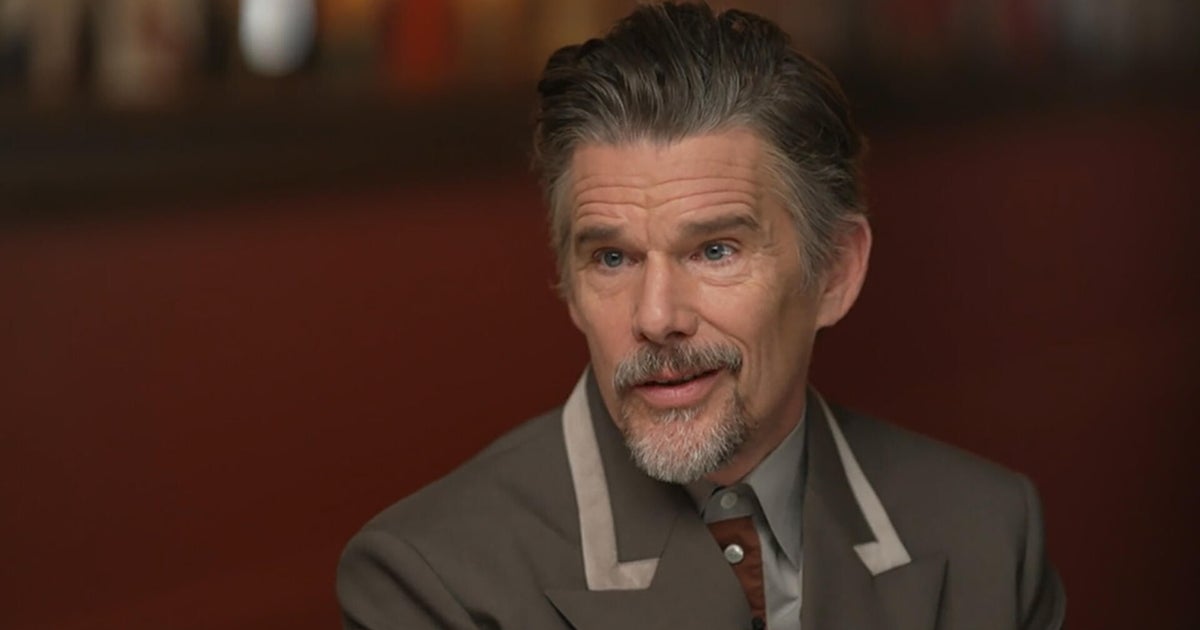

Professor Anders Eriksson, one of the authors of an influential 2016 study by the Swedish health technology agency, told the Diagnosing Murder podcast the study found the evidence for a diagnosis that has imprisoned hundreds of Australians was “very weak”.

Anders Eriksson, a retired professor of forensic medicine at the University of Umea in Sweden. He gave evidence in a landmark appeal court hearing in Victoria.

Forty researchers examined more than 3000 pieces of scientific literature in multiple languages for the 2016 study by the Swedish government agency (SBU). Their two-year review found the orthodox diagnosis – that a so-called “triad” of injuries points to child abuse – could not be scientifically confirmed.

When Eriksson and two other Scandinavian experts gave evidence in a Victorian Court of Appeal case in 2021, the majority judges dismissed their testimony as being “of little assistance”. The appeal had been brought by a young man, Jesse Vinaccia, who is serving an 8½-year sentence for child homicide after being found guilty of shaking his girlfriend’s baby to death.

Justices Jack Forrest and Karin Emerton found: “The SBU Report is radical in its approach and conclusions … It seeks to set aside decades of study … and the widespread acceptance that [shaken baby syndrome] may cause the constellation of clinical features known as ‘the triad’.

“Even if the evidence of the Scandinavian witnesses represents a respectable body of scientific opinion, which we doubt, it would do no more than stand against another respectable body of scientific opinion.”

Jesse Vinaccia (right) was jailed over the death of baby Kaleb Baylis-Clarke.

Responding for the first time to the critique, Eriksson told the podcast’s second episode, released today: “Who are these legal advisers, or judges? Who are they to tell us what science should do? I mean, it’s off the wall. They are not qualified [as scientists]. Period. It’s embarrassing – ignorant and embarrassing.”

Eriksson, now a retired professor and former member of the National Board of Forensic Medicine in Sweden, told Diagnosing Murder that the SBU was “one of the world’s oldest and most respected health technology agencies”.

Its review found most of the studies that purported to support the shaken baby theory were based on circular reasoning – the cases studied were only there because they had already been diagnosed as victims of abuse. This made the findings a “self-fulfilling prophecy”, Eriksson said.

In Sweden, prosecutions for the syndrome, which is now often called abusive, or inflicted, head trauma, had virtually stopped, he said.

Robert Roberson, whose execution in Texas was recently postponed over questions about shaken baby science. Credit: AP

“The [Swedish] Supreme Court said that to convict someone for shaking a baby, the medical findings are not enough – they’re not reliable enough,” he said. They would need other forms of evidence, such as witnesses, to prove the abuse.

Questions have also been consistently raised in courts in the United States. Last week, a Texas appeal court halted the execution of Robert Roberson, who had been convicted of shaking his daughter to death in 2002. The court found the conviction might conflict with the state’s “junk science” law.

However, in Australia, data compiled and reviewed by the podcast shows hundreds of parents have lost their children or been imprisoned over the past three decades based on the diagnosis.

The 2021 Victorian Appeal Court case was the first time the diagnosis itself – as opposed to simply an individual case – had been challenged. Appeal court decisions help settle legal precedents.

Norman Guthkelch, a pediatric neurosurgeon who first identified shaken baby syndrome but later reversed his view.

Diagnosing Murder also tells the story today of how the man who first theorised about a link between shaking and brain injury, British neurosurgeon Norman Guthkelch, later reversed his position.

Arizona Innocence Project lawyer Carrie Sperling told the podcast she had brought Guthkelch into a case of a young father convicted of murder in 2011. After the British doctor examined the case, he wrote in his expert report: “I wouldn’t hang a cat on the evidence of shaking as presented.”

His flip did not change the minds of the syndrome’s proponents. Instead, says Sperling, they dismissed him as being “senile … a lonely old man who got taken advantage of by lying defence attorneys”.

The podcast interviews one of the first people globally to question the research base for shaken baby syndrome, Sydney physician, Mark Donohoe. He first identified the circular reasoning problem in a paper in 2003.

Donohoe told Diagnosing Murder he also had been shot down, adding that medicine was too often based on the voice of authority, not scientific inquiry.

“We know that it takes 50 years to get a good idea in [to medicine] and 100 years to get a bad idea out,” Donohoe said. “That’s just the nature of our being a conservative medical community.”

When Eriksson and Scandinavian co-authors published their findings, they were quickly dismissed.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health in the United Kingdom issued a “consensus statement” that accused them of “excluding nearly all of the available learning”, posing a clinically irrelevant question, conducting an inadequate literature search and designing their research poorly. The majority judges in Vinaccia’s case quoted the statement.

The 16-week-old baby in that case, Kaleb Baylis-Clarke, was born small and unwell. In the lead-up to his death, his head had swollen “at a concerning rate”, according to one doctor, from the third percentile to the 85th percentile. This was no claim that this was the result of abuse.

Kaleb spent three days being treated in hospital for vomiting, drowsiness and the swollen head, before being sent home. Three days later, Vinaccia says he found Kaleb floppy and unresponsive one morning in his cot. Kaleb had no bruises and no fractures, and his head was even bigger.

Vinaccia told police he had picked Kaleb up “with a bit of force” the night before his death, and to have put him down in his cot “pretty rough”. The prosecution expert at the appeal acknowledged these actions could not have caused his injuries, so he must have been violently shaken.

Loading

Vinaccia’s lawyers argued Kaleb’s existing medical issues were a more likely reason for his death.

The majority judges found the prosecution case “cogent and reliable”. The third, minority, judge, former Victorian solicitor-general Kristen Walker, disagreed. She found Vinaccia had been the victim of a “substantial miscarriage of justice” and he should be immediately released.

Vinaccia will be released from prison later this month after serving his full sentence.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

Loading